The basics of the Catalan language

Languages are far more than just a method of communication between humans. Shared languages allow for shared customs, creating a set of beliefs and traditions that are the base of a society.

In a few words, a language is a symbol of identity, and this is particularly true in the case of Catalan.

Multiple times on the brink of extinction, this language was rescued through strenuous efforts and dedication from its native speakers, making it a symbol of pride and cultural togetherness.

A language that is spoken beyond Spain’s borders.

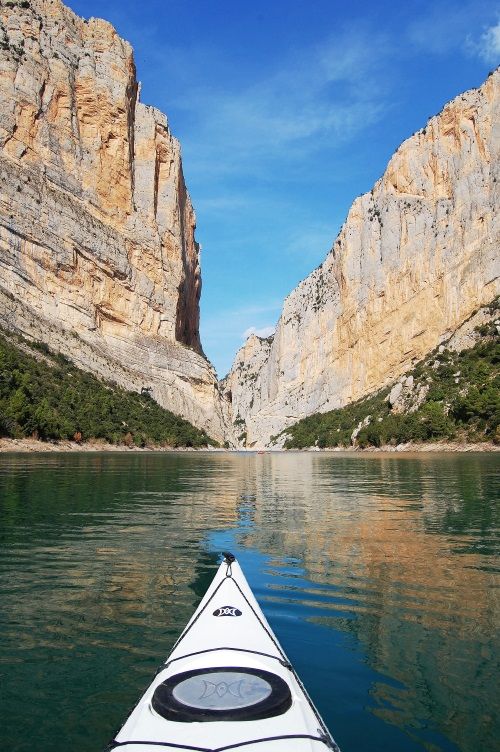

Catalan as a language spreads through the so-called Països Catalanes, a community of territories on the northeast region of Spain around the Pyrenees, and several islands on the Mediterranean.

The Principality of Andorra has Catalan as its only official language, while in Spain it is an official regional language in the autonomous communities of Catalonia, Valencia, and the Balearic Islands.

Likewise, in 2017 the French department of Pyrénées-Orientales acknowledged Catalan as an official language within its territory, and the Italian town of Alghero speaks an officially-recognized dialect of Catalan called Algherese.

In total, it is assumed that through most of these areas, over seven million people speak Catalan fluently, and over ten million understand it.

Catalan is not a dialect of Spanish.

Since Catalan is often associated with Barcelona and other Spanish cities, it’s common for people to assume both languages are intimately related. However, the truth is that Catalan differs from Spanish in origins and evolution.

Catalan is, as many other languages in Europe, a Romance language, meaning that it evolved from Vulgar Latin, a variant of Latin spoken in the Mediterranean.

While both Spanish and Catalan are Western Romance languages, that’s where the similarity ends. Spanish belongs to the subgroup of Iberian Romance languages, while Catalan is in the Gallo-Romance one, alongside French.

This branching system is not aleatory, and while there are many connections between Spanish and Catalan due to their proximity, Catalan resembles French more closely. Likewise, Catalan lacks the strong Arab influence that Spanish received, therefore creating a large gap between both tongues.

However, Catalan has many dialects.

As expected from a language spoken in different countries and geographical areas, Catalan exhibits many variations. While the differences between the dialects are not profound, they are significant enough for experts to divide the language into two broad groups.

Eastern Catalan comprises four different dialects: Central (spoken mostly on the Spanish provinces of Barcelona, Gerona, and some parts of Tarragona), Balearic (exclusive to the Spanish Balearic Islands), Rossellonese (the Roussillon area of the French Pyrénées-Orientales), and the previously discussed Alguerese (spoken in Alghero, Italy.).

On the other hand, Western Catalan includes two dialects: Valencian (spoken in the Autonomous Community of Valencia), and Northwestern (Andorra, the Spanish provinces of Leida, and parts of Aragon and Tarragona.)

Catalan is an old language with a rich history.

The oldest document with recorded use of Catalan dates from the 12th century, with its use spreading in poetry during the 13th century. As the Principality of Catalonia flourished and expanded under Aragon’s rule, so did the language—as they conquered Valencia, the Balearic Islands, and areas of Sardinia, they left Catalan behind.

However, the union of the crowns of Aragon and Castile—marking the start of what would become Spain—begun Catalan’s decline as a widespread European language. After Spain ceded North Catalonia to France in 1659, the French government attempted to impose French on the area, starting a campaign to erase the use of Catalan.

The remaining territories within Spain didn’t fare much better—with Castile’s power increasing, its language imposed over the rest, including Catalan, whose declining use eventually hit rock bottom.

La Decadència was almost the end of Catalan.

In the early 18th-century, a conflict known as the War of Spanish Succession had Castile and Aragon fighting within Spain to proclaim a new king. Castile eventually won, and the newly-crowned king imposed measures that aimed to centralize Spain and unify it as a single entity.

While this helped establish Spain as a country, it also started a period of progressive decline and use of Catalan, known as la decadència.

Castilian—later known as Spanish—became the official language for Catalonia’s government and judicial system, therefore reducing the need for Catalan and outright discouraging its use.

La Renaixença, Modernisme and Noucentisme marked its revival.

After hitting rock bottom, the only way is up—and in the 19th century, the banning of Catalan encouraged a younger generation to promote its use.

The publication of Gramatica y Apología de la Llengua Cathalana by Josep Pau Ballot marked the start of a movement named la renaixença, noted as the start of an era of prosperity of the language. Books and essays on Catalan were encouraged, as well as poetry and fiction that promoted traditionalism and Catalan pride.

In the early 20th century, an art and literature movement named Modernisme took over, revindicating the language and opposing the traditionalism of la renaixença, while subsequently, Noucentisme appeared as a reaction to Modernisme.

These three movements, while vastly different, encouraged the use of Catalan and took pride in the language and identity.

Franco’s dictatorship was the final obstacle to overcome.

The Catalan language continued to thrive and got officially recognized as a language by the short-lived Second Spanish Republic, but it all came to an end with the establishment of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship.

Franco’s regime forbid the use of Catalan through most available means—forced television, film, music, and books to use Spanish, Catalan streets and locations got assigned new names, and speaking the language in private was thoroughly discouraged, up until his death in 1975.

With the transition of Spain towards democracy began a new era for Catalan—now recognized as an official language, the government implemented multiple programs to reintroduce it to schools, media, and daily usage.

The Catalan language has some distinguishable sounds and symbols.

To someone that doesn’t speak Romance languages, Catalan may seem similar to Spanish or French, mostly because they share multiple sounds and symbols. However, do not be fooled—Catalan is a unique language.

These are some of the most distinguishable traits of Catalan, some found in other similar languages, and some exclusive.

The presence of the ç.

Known in Catalan as ce trencada, this letter appears in the French alphabet as well, yet has a different use.

The Catalan language places it before “a”, “o”, or “u”, or at the end of the word. It is pronounced akin to a hissing “s”.

There is no ñ.

Unlike Spanish, Catalan does not have the typical “ñ” letter. However, the phonetics exist—spelled as “nya”.

For example, Catalonia is the English name of Catalunya, while the Spanish spell it as Cataluña.

The “ch” phonetic is spelled as “x”.

The sound given to the “x” letter in Catalan is unlike any other—it resembles the Spanish and English “ch”.

For example, in Catalan, chocolate is spelled with an x—xocolate, while chorizo becomes xoriço.

The use of “L·L” and “LL”.

While similar, they are reasonably different and evoke completely different sounds.

The “L·L” is named ele geminada in Catalan, and it’s exclusive of the language. It is always between two vowels, and it represents the sound of an elongated “L” that stretches between two syllables.

While it is correct to stretch the “L” sound, in fast speak, it is often not emphasized.

For example, movie in English becomes pel·lícula in Catalán.

On the other hand, the double L or “LL” has a sound that is distinctively Catalan—its pronunciation is akin to a soft Spanish “LL”, but placing your flat tongue against the back of your upper teeth.

To non-native speakers this is one of the hardest sounds to learn, as the phonetic is rather uncommon.

Some unique expressions in Catalan.

Not everything has to be basic, useful terms—you can find those on Google Translate. Part of the joy of languages is the existence of expressions that cannot be properly translated. Here are some iconic ones in Catalan.

S’ha acabat el bròquil.

Literally meaning “there is no more broccoli”, this phrase is used to point out that something finished, usually a deception or mischief.

He begut oli.

Means “I drank oil”, and usually expresses disappointment at a failure.

Quatre gats.

“Four cats” in Catalan, It’s often used to indicate there were only a few people at a particular place.

Salut i força al canut.

This is the most widespread Catalan toast, and it has acquired cheeky double meaning.

Literally, it says “health, and strength to the canut”—the canut being an old type of purse leather used to store coins, therefore the original meaning of the cheer wishes for health and financial success. However, a similarity with the Spanish word canuto has widespread the double entendre of wishing for health and virility.

Conclusion? The value of Catalan isn’t in its widespread use.

With a little over ten million people able to understand it, Catalan is not one of the most commonly spoken languages across the world. However, thinking this diminishes its value it’s a reductionist point of view.

Catalan has thrived and survived despite adversity, becoming synonymous with resistance in the face of cultural suppression.

Learning Catalan is learning a language that refused to die, and stepping closer to a culture that insists of thriving.

English

English

Català

Català